Robots in the Kitchen: Philosophy Faculty Host Vatican Workshop on Emerging Tech

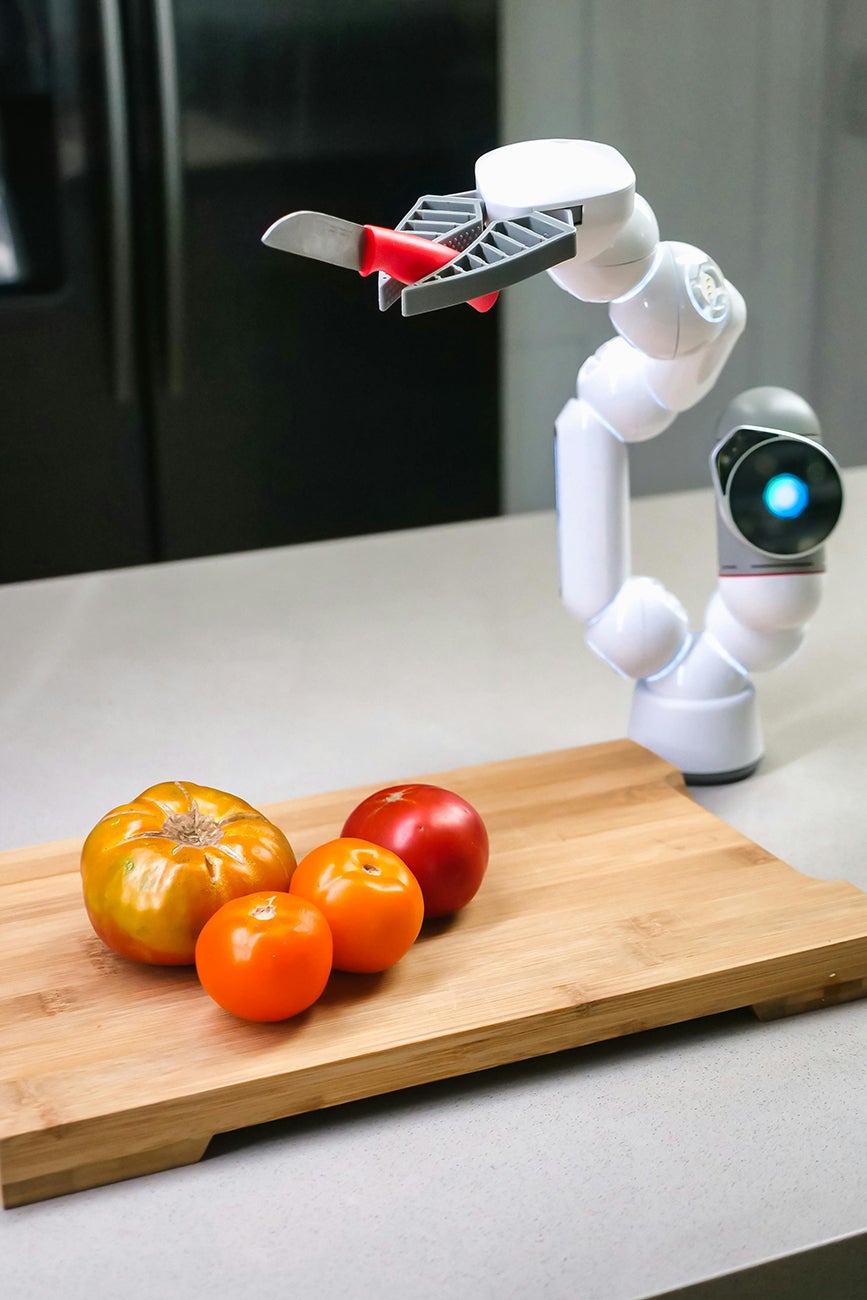

Picture this: You’re waiting excitedly for a table at your town’s hottest pop-up restaurant, eager to try a famous specialty created by a Michelin-starred celebrity chef. Only you don’t have to travel to her fine-dining restaurant in Europe. She’s licensed her recipe — in fact, every intricate step in her cooking process — to a service that has trained a fleet of robot cooks to flawlessly replicate her precise movements. You’re about to enjoy a dish made famous half a world away, in your own hometown, at a fraction of the price — but it’s prepared by a robot.

The technology in this imagined scenario is not far off. What will we have gained in this future? And just as importantly, what will we have lost?

In May, philosophy professors Patrick Lin and Daniel Story, religious studies professor Anya Foxen and psychology professor Jennifer Jipson will travel to Rome to discuss these questions and many more at an interdisciplinary workshop hosted by the Vatican. The faculty team will meet with scientists, industry experts, religious leaders and philosophers from around the world to discuss the ethical impacts of automation and artificial intelligence on how our food is made.

It’s part of a multi-year research project by Cal Poly’s Ethics + Emerging Sciences study group, funded by a grant from the National Science Foundation, to examine the ethical implications of robotic and AI applications in the kitchen. The project involves input from faculty from around Cal Poly, including food science, psychology, religious studies and gender studies professors.

“This is our most interdisciplinary project, which isn't a surprise because the subject, food itself, touches on just about every single discipline at Cal Poly,” said Lin.

While automation has long had a place in many aspects of the food industry, this project is focused on cutting-edge and near-future developments in what the researchers call “the last mile” of the food value chain: menu development and meal preparation.

Such technologies range from robotic arms programmed to perform one process, like flipping burgers or peeling avocados, to technologies capable of cooking an entire meal. They also include AI applications for creating new recipes and quantifying kitchen tasks and data to the most minute detail.

Last fall, the study group published an article in The Conversation recapping the first stages of their research and outlining the stakes of the issue, which was reposted in high-profile publications around the world, including Salon, Fast Company and Smithsonian Magazine.

“Our study seems very futuristic, but some of these technologies are already being adopted by restaurants,” said Lin. “So we want to imagine the future. What if this trend continues and it really takes off? What are the kinds of disruptions we can anticipate?”

The potential benefits of this technology are easy to see: more labor efficiency for both home cooks and food-based businesses; less human error in food safety, reducing the incidence of foodborne illness; and less time spent in the kitchen that could be better spent with friends and family.

The potential benefits of this technology are easy to see: more labor efficiency for both home cooks and food-based businesses; less human error in food safety, reducing the incidence of foodborne illness; and less time spent in the kitchen that could be better spent with friends and family.

There are even opportunities for personalized nutrition, currently only available to those who can afford a team of personal chefs and dietitians.

In the near future, an average diner might be able to go to a restaurant and scan a personal code that would upload their individual set of dietary needs, prompting an automated kitchen to create a nutritionally perfect meal just for them.

“We see potential for great benefits in the technology, but also potential for some serious and harmful disruptions — and we want to try to balance out the two,” said Lin.

A downside of greater efficiency, for example, is a potential loss of opportunity for human workers. Every dollar of labor saved by a food company represents a dollar not paid to an employee — likely in key entry-level jobs that often launch the careers of students, immigrants or single parents. What happens to your teen’s workplace skills when what might have been their first restaurant or coffee shop job goes instead to an automated kiosk?

“Food service isn’t just a popular job — it’s a unique and valuable gateway into the economy,” said Lin.

Another ethical concern is a phenomenon called “reverse adaptation,” in which interchangeable, unskilled human labor is used to facilitate an automated technological process, rather than the automated technology being used as a tool to assist a human objective.

An example of this is CloudChef, a tech startup that seeks to, in its own words, “codify the intuition of the chef.”

Using AI technology, CloudChef records the process of a top chef preparing a signature dish, then breaks the process down into specific prompts to be followed by an employee who can then mass-produce the dish at a cheaper rate — without ever having to know how to cook.

“This is the sort of model of labor that we often see in Amazon warehouses, because it's more efficient for laborers to be interchangeable,” said Story. “That can be alienating and can make work miserable or boring or menial in a different way. And I think this is something we should seriously worry about.”

Another risk point involves surveillance. A key component of developing effective automated cooking technology is mountains of data — which means precise monitoring of people who currently do that work. Many studies have shown that more supervision in the workplace leads to more dissatisfaction for the employees being watched.

And it’s not just the food creators being watched. Diners taking advantage of automated food preparation might be generating tons of precise data about their eating habits. Who might want to purchase such information? What might happen if your employer or health insurance company could see a detailed list of everything you ate?

We see potential for great benefits in the technology, but also potential for some serious and harmful disruptions — and we want to try to balance out the two.

Of key concern to the study is what happens to general quality of life if one of humankind’s most fundamental experiences becomes automated by technology.

“Oftentimes the value and pleasure we get out of eating food is inflected by our beliefs about how it's connected to community or our beliefs about who made it,” said Story. “If you're at a family dinner and your parents or grandparents made a meal, your experience of eating that food is going to be affected by your knowledge that this was made by someone who loves you in the context of this loving family event. Technological advancements might change the literal experience of eating and what you get out of your food.”

That concept extends beyond the family to a cultural level.

“Think about your favorite cities and towns around the world,” said Lin. “Chances are, you're also thinking about some of the restaurants, cafes or street food you’ve had there. That is part of the experience of enjoying the character of a neighborhood or a culture. No one remembers a city because of the awesome robotic kiosk that they got a pizza from once.”

Lin and Story explore these questions because oftentimes, tech companies are too focused on what they can achieve to stop and wonder whether they should achieve it. Their work is meant to help tech companies, as well as policymakers and the public, more effectively evaluate the potential risks and rewards of new technology.

Perhaps nowhere is that deliberation more important than in technology that affects our relationship with food.

“Food is one of the most basic things to human life, next to air and water,” said Lin. “The kitchen has a special place in the home and in communities. We need to pay extra attention to that, because it has the potential to be much more disruptive to our society than other technologies. It’s a deeply human subject and automating anything around that could have serious unknown effects.”

Want more Learn by Doing stories in your life? Sign up for our monthly newsletter, the Cal Poly News Recap!