‘A Massive Team Effort’ — Inside Cal Poly’s New Saliva-Based COVID Testing Program

Last week, Cal Poly’s COVID-19 testing capacity got a major upgrade as the university transitioned from an outside vendor to a new, faculty-developed saliva-based surveillance test and on-campus laboratory — enabling faster processing and providing a valuable Learn by Doing experience in the process.

The new test provides several key improvements over the university’s previous model. First, as a saliva-based test rather than a nasal swab, the testing experience is more comfortable and less invasive, and reduces time on-site for individuals getting tested.

More importantly, the new test significantly increases the volume of samples that can be processed and reduces wait times for results to under 24 hours, allowing university health staff to more effectively catch infections before they spread. It’s also an invaluable factor in the university’s goal to achieve biweekly testing for more than 4,000 students, and eventually more as campus protocols evolve with the pandemic.

“At full scale, we will be processing at minimum 4,000 individual samples in roughly eight hours,” said Nathaniel Martinez, a biology professor and the lead researcher on the team that developed the new protocols.

As of Feb. 25, all students are now being tested using the new saliva method. Faculty and staff members will also transition to the new method in the coming weeks.

Martinez and a team of faculty members, mainly in the biology department, developed the test based on existing reverse transcription quantitative polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR) technology — a proven technique that is the gold standard in COVID-19 detection. The faculty team worked with other universities who had developed similar saliva-based protocols in order to customize the test to Cal Poly’s unique circumstances.

“The protocol is a modified version of the SalivaDirect protocol, which comes from Yale,” said Martinez. “We modified and adapted it to our instruments and to be performed by Cal Poly faculty.”

To validate the new version of the test, the team worked with Kevin Ferguson, a pathologist at Marian Medical Center in nearby Santa Maria, California, and one of the Central Coast’s leading pathology experts. Preliminary results obtained from the Cal Poly test conformed closely to Ferguson’s results of the same samples, yielding a 93% sensitivity rate and a 97% specificity rate, which means that the test is highly accurate and precise.

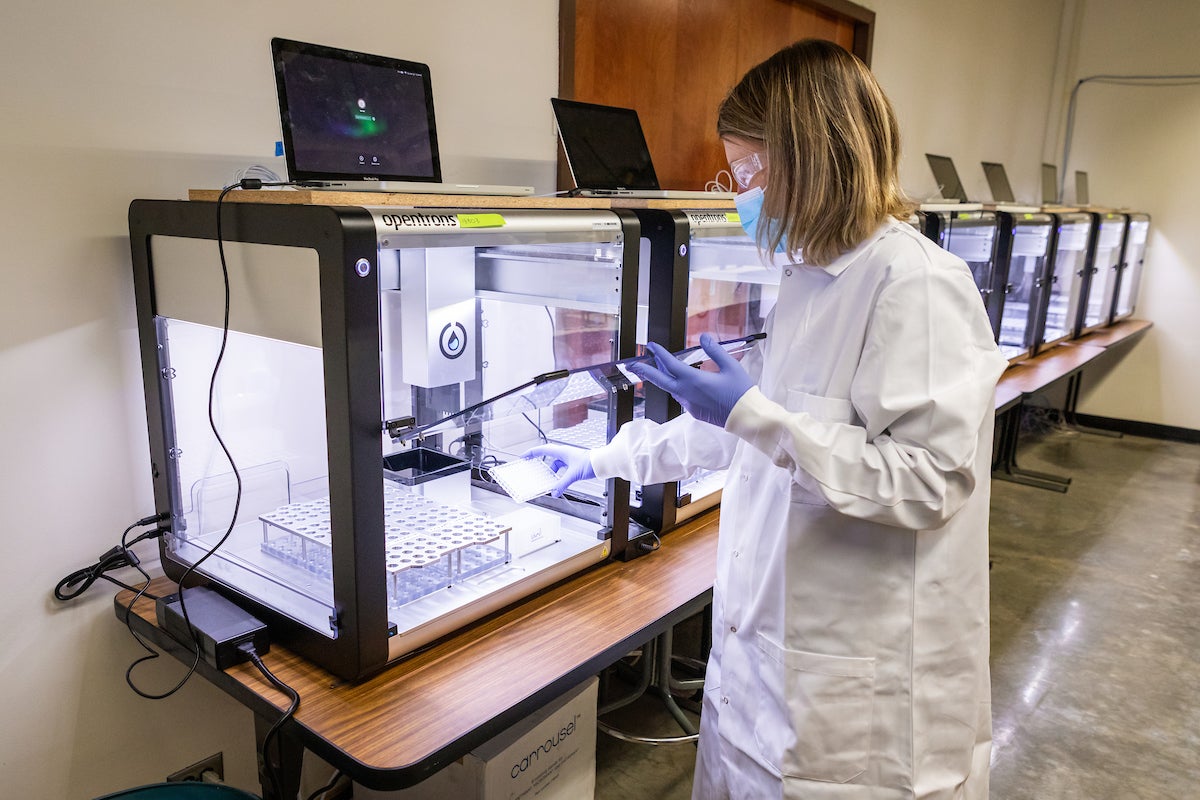

Thanks to the efforts of faculty with expertise in robotics, including biologist Jean Davidson and biochemist Javin Oza, the process is highly automated — a critical component in producing not just an accurate test, but also one that can scale large enough to process the thousands of samples necessary to eventually get the campus back to full capacity.

“You're just not going to be able to do this without technology,” said Davidson. “And so we’re working on the best implementation that maintains security, maintains accuracy, and gets us to that huge throughput number.”

At every point in the process, samples are guided by a series of barcodes, handled by robots programmed to precisely and efficiently deliver and process large batches, and protected by rigorous security protocols for both machines and human lab technicians.

“I'm really proud of our protocol — it is unique,” said Davidson. “No one else is relying quite as much on robots as we are, and that's having some really important consequences. We are able to do it much more efficiently and much faster than other institutions.”

In addition to being a critical resource for protecting campus health, the new surveillance protocols provide into an incredible Learn by Doing opportunity for students interested in fields like microbiology, public health and clinical science. While much of the process is automated, human input is needed at many points, from sample collection to lab work to programming, and students are providing much of that work.

Vinay Gopan is a third-year microbiology student who joined the project in November. He had hoped to join Martinez for a more standard research lab experience — currently on hold due to the pandemic — when the professor reached out to him for another opportunity.

Initially, Gopan’s duties centered on soliciting and collecting saliva samples from other students, which the team would use to validate the effectiveness of the test, comparing the results from the new protocols with results gained from more conventional nasal swab tests.

“I've taken a lot of labs as classes that have prepared me for this, but I haven't done anything like this in terms of research,” said Gopan. “It's cool to actually apply what you did in a lab class to real life. The stakes are obviously a little higher in this version.”

Today, Gopan’s responsibilities run the breadth of the entire project. On any given day, he might be interacting with clients at the sample collection station, preparing samples for testing, or running tests in the lab — all valuable experience as he prepares for a career in medicine and infectious disease research.

“This has been a really great experience for exposure to different environments, whether it's a lab setting or a healthcare setting, and just seeing how things work and being a part of that,” he said.

The saliva-based surveillance program is just one way the university is working to keep the campus safe. Cal Poly has also implemented wastewater testing to monitor potential outbreaks before they spread.

Starting in late fall, facilities staff and faculty worked together to deploy five testing units at main junctions of the campus sewer system to monitor wastewater flowing from the residential areas. The units look for traces of SARS-CoV-2 RNA in the residential waste, indicating a possible infection among the student population.

“The wastewater gives us more of a broad glance at where there might be problems,” said Martinez. “If we start to see infections in the wastewater testing, then we can do more targeted saliva testing — even, say, to a specific dorm.”

According to Aydin Nazmi, an epidemiologist and presidential faculty fellow overseeing Cal Poly's COVID-19 response, the entire project has been a giant lift for the faculty and staff involved — and only possible because of the breadth of expertise available on campus.

“We just have the right people to pull this off,” he said. “It's a combination of luck and grit, because this group of people stepped up to take this on, in addition to everything else they were doing during fall quarter.”

“It's a massive team effort — this is something that crosses every barrier and boundary of Cal Poly, from students to faculty to facilities and maintenance staff,” said Martinez. “Our hope is that, because of the high levels of testing that we will be able to achieve, that we will be able to quell any potential outbreak, get all of our students back in the classroom, and be able to have our campus back.”