Ask an Expert: How Do You Vote in a Pandemic?

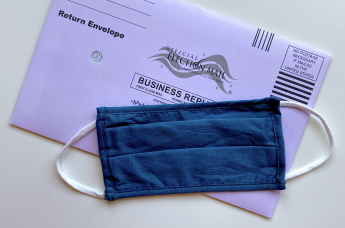

With a presidential election just months away and a pandemic keeping many Americans away from public spaces, the ability to vote safely and securely has become a major concern for engaged voters around the nation.

Cal Poly political science professor Mike Latner is a nationally-recognized expert on voting rights. He works with the Union of Concerned Scientists on developing policy proposals to combat voting inequality, and is the co-author of the book “Gerrymandering in America: The House of Representatives, the Supreme Court and the Future of Popular Sovereignty.”

Latner met with Cal Poly News to help separate fact from fiction in the conversation about voting by mail, and discuss how the nation can address the challenges that are sure to arise in this unprecedented election.

How does voting by mail work? Is it as susceptible to fraud as some people claim? There are a variety of types of voting by mail. The most comprehensive is what we call universal vote by mail. That’s a system in five states — Washington, Oregon, Utah, Colorado and Hawaii — where every eligible voter receives a ballot in the mail. California is moving to universal vote by mail for this coming November election.

In Oregon, counties put secure drop boxes in various locations, and any voter can turn their ballot directly in to a drop box. The other option is California’s traditional model, which is no-fault absentee voting. That means if you’re a registered voter in California, for any reason or no reason at all, you can sign up to be a permanent absentee voter and have your ballot mailed to you.

All states have some form of mail-in voting, for military voters and overseas voters. It’s important to note though, that even in the universal vote-by-mail states, there are opportunities to vote in person.

On voter fraud, I did some work with the UCLA Voting Rights Project, and there have been several other studies as well that have looked at vote by mail as a process. And when we look across states where more people vote by mail, we don't see any evidence that there's a significant increase of voter fraud.

If anything, the real concern is when we move a bunch of people into a different system of voting, you're going to have mistakes. You may have a higher ballot rejection rate because of differences between signatures on ballots and registration files. But generally speaking, voter fraud is not a problem in the United States.

What lessons should we learn from recent primary elections this year about voting in a pandemic? Particularly primaries like Georgia and Michigan, where there were serious problems at polling places with overcrowding and polls closing? I'm currently working on a study where political scientists and economists looked at the Wisconsin primary, where we had exactly this pattern. The city of Milwaukee consolidated their polling places — they went from about 85 polling places to just five. Because of the pandemic, a lot of people requested mail-in ballots, but the state wasn’t prepared for it in a number of ways. People were waiting on Election Day to get ballots in the mail that they had never came. The governor tried to postpone the election, which was rejected in the courts, but it wasn’t even clear the day before whether there would be an election at all.

So you had all this last minute confusion, and then you had voters that were standing in line for four hours at a time. Two and three weeks after the election, the counties where you had larger numbers of people per polling place showed a spike in positive cases of COVID-19.

We know that this threat is real and it's something that we have to take account for November, if we are looking to stop the spread of the disease and to ensure that people can safely exercise their franchise.

If every additional administrative step is going to make voting harder, what does that actually mean in terms of who effectively ends up being able to vote? The way we look at it in political science is that every act has a cost. If you have to take time out of your day, or if there’s only a certain day or place where you can vote, or only a certain way to get election information, every little thing that makes it more difficult goes into this calculus of whether or not someone votes.

If everyone starts out with the same resources — money, time, whatever — then the cost of voting is the same for everyone. But we know that we already have inequalities, people who have fewer resources like free time. So when you have those inequalities in society already and then add the cost of voting on top of it, it’s more difficult for people of lower socioeconomic status, people in communities that are less well-served, to overcome this cost.

What ends up happening is that you end up exacerbating the inequalities that are already present in the system. That's really what we want to avoid because that's a question of equity, and it's frankly a question of voting rights and political equality.

What do we need to be looking out for in the upcoming November election, with everything going on? The first thing we need to do is to make it easier to register to vote. The demand is certainly there — if you look at polling data, this will probably be a record year for voter turnout, if we have the infrastructure set up

Second, we need to make it easier to vote by mail. We should be sending all registered voters mail-in ballots, and not make them go through the process of having to request them, because every extra step in the process leads to fewer people actually turning out to vote.

Third, we need to ensure security and safety at the polls. That means we need to be as efficient as possible in processing voters in person on election day. We need reliable, working voting machines, sanitation, social distancing and safety guidelines. The goal needs to be minimizing wait time, because that’s where the greatest risk is.

And finally, we need an open and transparent process with regard to processing ballots, because across the United States election officials are going to be facing problems that they’ve never faced before. We know that voters of color and younger or first-time voters are most likely to have their ballots rejected. Especially in this political environment, we need to make sure that the process is fair, transparent and equitable.

For all that to work together, what the states need more than anything else is support from Congress. The CARES Act allocated about $400 million in election support to the states. We’ve found that we actually need about $4 billion allocated across all 50 states in order to ensure a safe and secure election.

Are there signs that more states are taking these issues seriously and working to address them? There are, in fact. There have been something like 42 states taking some kind of action to either reduce the excuses required to obtain an absentee ballot, or like in the state of Michigan, they're proactively sending eligible voters absentee ballot requests. You can see it happening around the country, but it’s slow.

My concern is that we're going to be in a position where even if states provide the necessary legislation, that there simply aren’t going to be the resources and the financial support that state and local election officials need. Congress needs to allocate more support for this effort nationwide, because states can only do so much. And we have to act now if the nation's going to be ready in November.